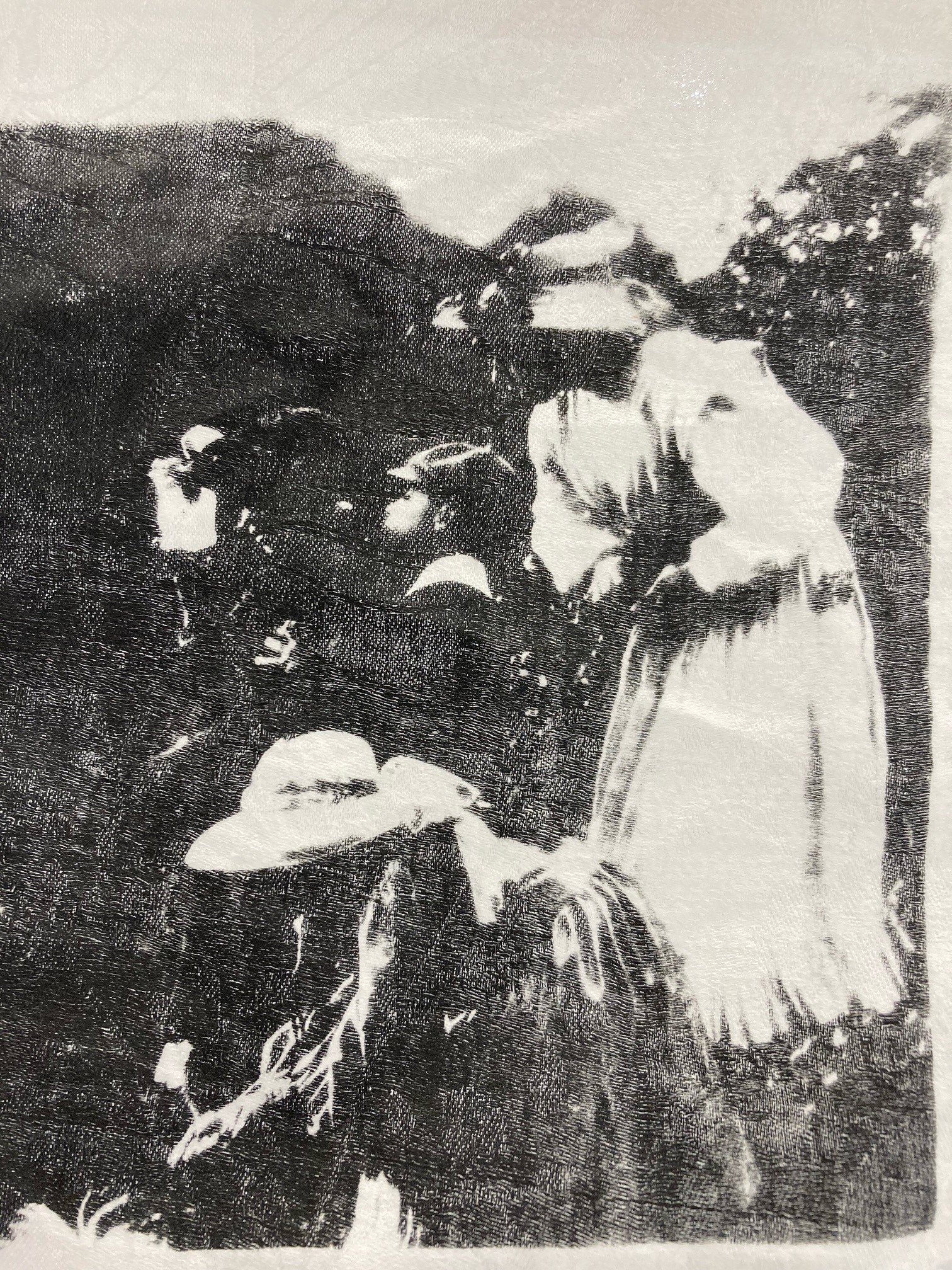

Ladies at work in the Templeton Carpet Factory.

Ruby McDivit

‘My aunt Ruby used to work at Templeton Carpet Factory around 1931 - 1939. They made carpets for Clyde shipbuilding.

She always said she enjoyed working with friends - though it was very noisy. Workers made their own entertainment and sang as they worked. It was mostly women who hated working for the men, who were misogynistic and lecherous.

None of them wanted to be left alone with a foreman, women were always in groups for protection. Your whole life would have been dependent on that job, so you didn’t really have any footing to speak out about these men’s behaviour.

Some other relatives of mine worked in other factories too.

Great Auntie Anna worked in a scarf factory called Gilfords, who employed hundreds of women around 1930’s.

There was a factory at the bottom of Allison Street that made Levi’s jeans. Again many women, they went on strike around 1973 as conditions were so bad.

Lizzie Beattie - the terror of the Calton - used to work in the singer sewing machine factory - her boyfriend died in the war, and she never did find anyone else.’

A top made from an old bed sheet, eco dyed with leaves, with sashiko stitched details.

Lindsey Anderson

‘During lockdown I discovered the work of India Flint online, and decided to give it a go for myself. I now make all of my own clothes from recycled textiles. From bedsheets to old jeans, I make new items decorated with natural dyes and stitching. There is so much experimentation with eco dying, it’s fascinating to see the results each plant can give.

I am involved with the Forgan Arts Centre in Newport-on-Tay, we’ve taken over an old care home and recently opened studios there. I have always been interested in gardening and the arts centre has lots of raised beds, I’ve taken one over to plant a dye garden, there’s another bed that has plants grown for fibre which will also be used in textile art. There are also weavers and other textile artists and designers at the centre, working and collaborating as a community.’

Second Cashmere - Visible mending with reclaimed cashmere yarn on the elbow of a 100% cashmere cardigan that was thrown out.

Sustainability in the fashion industry is a topic of increasing importance and interest. We talked to two modern women owned studio-based brands with sustainability at their heart about their practice.

Lotti Blades-Barrett

Lotti, from Second Cashmere spoke about why sustainability is important to her:

“Second Cashmere is a sustainable fashion brand with a sole focus on reducing and reusing textile waste. From developing our zero waste collections to our repair service, we hope to make a real difference in the way people shop and think about cashmere, especially when it comes to finding an alternative to fast fashion.”

“Podcasts [for the banter] are gold dust for us at Second Cashmere - can’t get enough of ‘em!”

The above research and interview reminded us particularly of villagers working together to make textiles in pre-industrial times, with the podcast a new way of connecting and listening virtually to stories whilst working individually.

Siobhan McKenna

Siobhan runs ReJean Denim, a zero waste bespoke denim brand. She spoke about a stitching technique she uses to upcycle and breathe new life into her recycled denim pieces:

‘Visible mending has been a part of our production practice for a while now. I guess it was inevitable that I would add this method to my practice. I first got into it at the start of the pandemic when we were all stuck at home. I learned more about sashiko and boro and its Japanese origins, about the correct needles and threads to use. I realised how important it is to get everyone to mend their clothes and the mental health and cost benefits of learning to do so. And since 2020 I have been offering repairs as part of the business. And in 2022 we properly kicked off the mending club in collaboration with Bawn Textiles, I love getting people in to mend their clothes. It always such a lovely wholesome evening of slow stitching and good chats.’

And on music:

‘I listen to music constantly in the studio. I find it really hard to work without any kind of background noise. When I’m in on my own I can have tune blaring on my headphones.

I listen to upbeat electronic music. Maybe house or techno most of the time.

When the girls are in, I change it up a bit. Lots of 90s pop, just whatever we fancy. I get into audiobooks too when I’ve rinsed all my music and I need a change.’

Rejean Denim - A stack of jeans, which are damaged and set to be reimagined by Rejean, some examples of Sashiko stitching in the pocket.

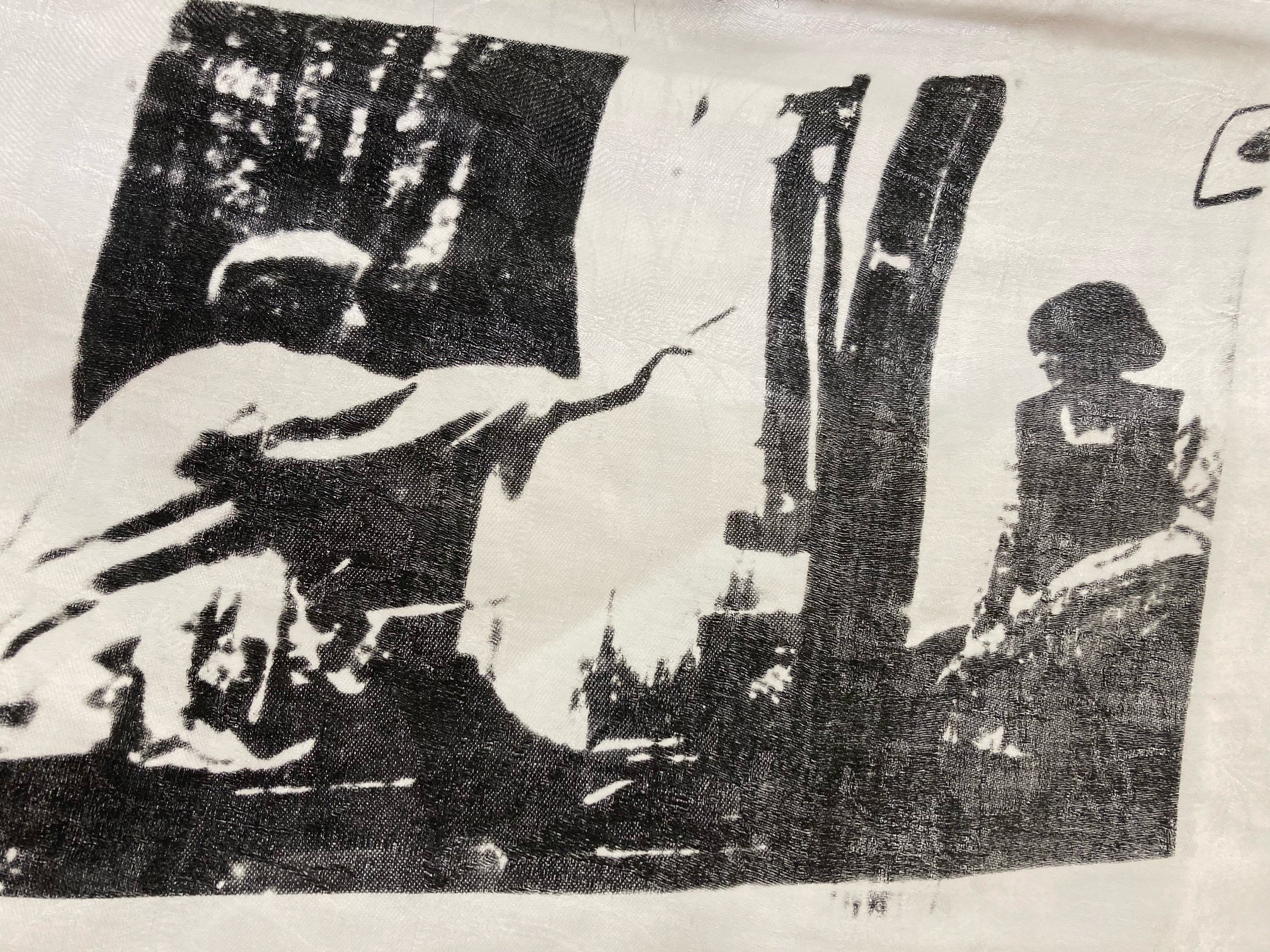

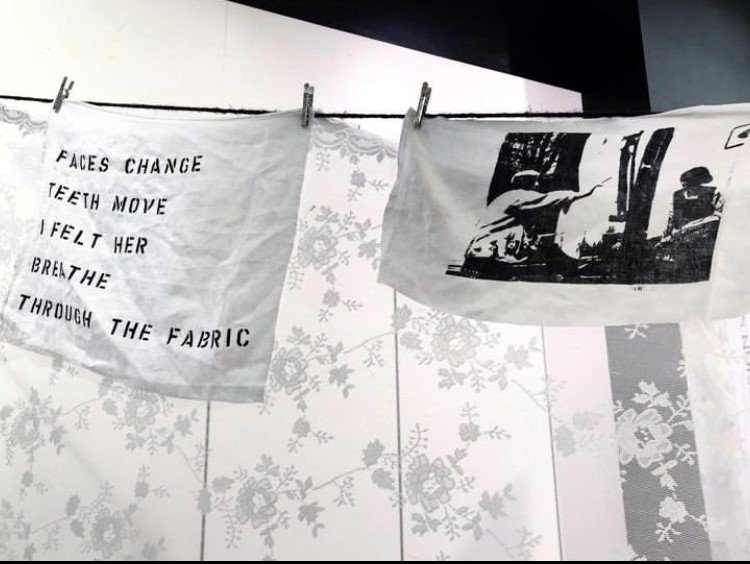

Tilda Watson’s There Is No Romance

Dundee based artist Tilda Watson was commissioned by us especially for our launch Exhibition to print and create an installation. Tilda researched and discovered one very special Scottish story, evocative of London’s Bloomsbury Set, into an installation in lace and print with the DCA Print Studio. Bridging the post World War 1 gap between our eras, the work illustrated an early 20th century easing of Victorian and Edwardian industrial scale global repression, uncovering the artist’s ancestor: ‘Glasgow Girl’ painter Cecile Walton’s hidden story. An unhappy marriage led to Cecile Walton travelling to Vienna and having a passionate relationship with artist Dorothy Johnstone, finally settling in Kirkcudbright, within the famous women’s community of artists founded by Scottish Arts & Crafts designer and illustrator Jessie M. King, another ‘Glasgow Girl’ artist. Renowned for working amid Art Nouveau, creating jewellery and ceramics designs for Liberty’s, King is also credited with influencing early Art Deco development whilst living in Paris, before moving and creating the women’s artist community Kirkcudbright, in Dumfries & Gallloway. The women there cut their hair radically short, and some kept their maiden names intentionally, despite having husbands, and one named Evelina Haverfield formed a Secret Lesbian Society.

Singer Sewing Machine - loaned for the Exhibition, original hand and foot treadle machine converted to electric by Singer, still working…

Michael

‘My mum used to have one of these Singers in the room, and sit at the back sewing everything for the family.

My gran was a weaver, and my grandad worked in the textiles too – went into the factories – Don & Lows in Forfar, polypropylene and all that he did.

I worked with the old Lairds* before they sold up and moved overseas, the guy as ran that went on to get knighted and all that, but I remember we went to Singer to do a job to fit a fire escape when the factory was still standing – absolutely huge it was, with that massive clock tower.

Bigger than London (Westminster)

All gone now.’

*Lairds the company is now a global concern owned by DuPont – with no base and zero premises in the UK.

Singer factory clock tower, Clydebank.

Visitors from Holland

‘I learned to sew on one of these Singer machines, I have such fond memories of it. I still have the electric machine I got for my 21st birthday… that was 50 years ago.

My son’s partner back at home does a lot of mending. She runs visible mending workshops to encourage others to get involved and are for their clothes too.’

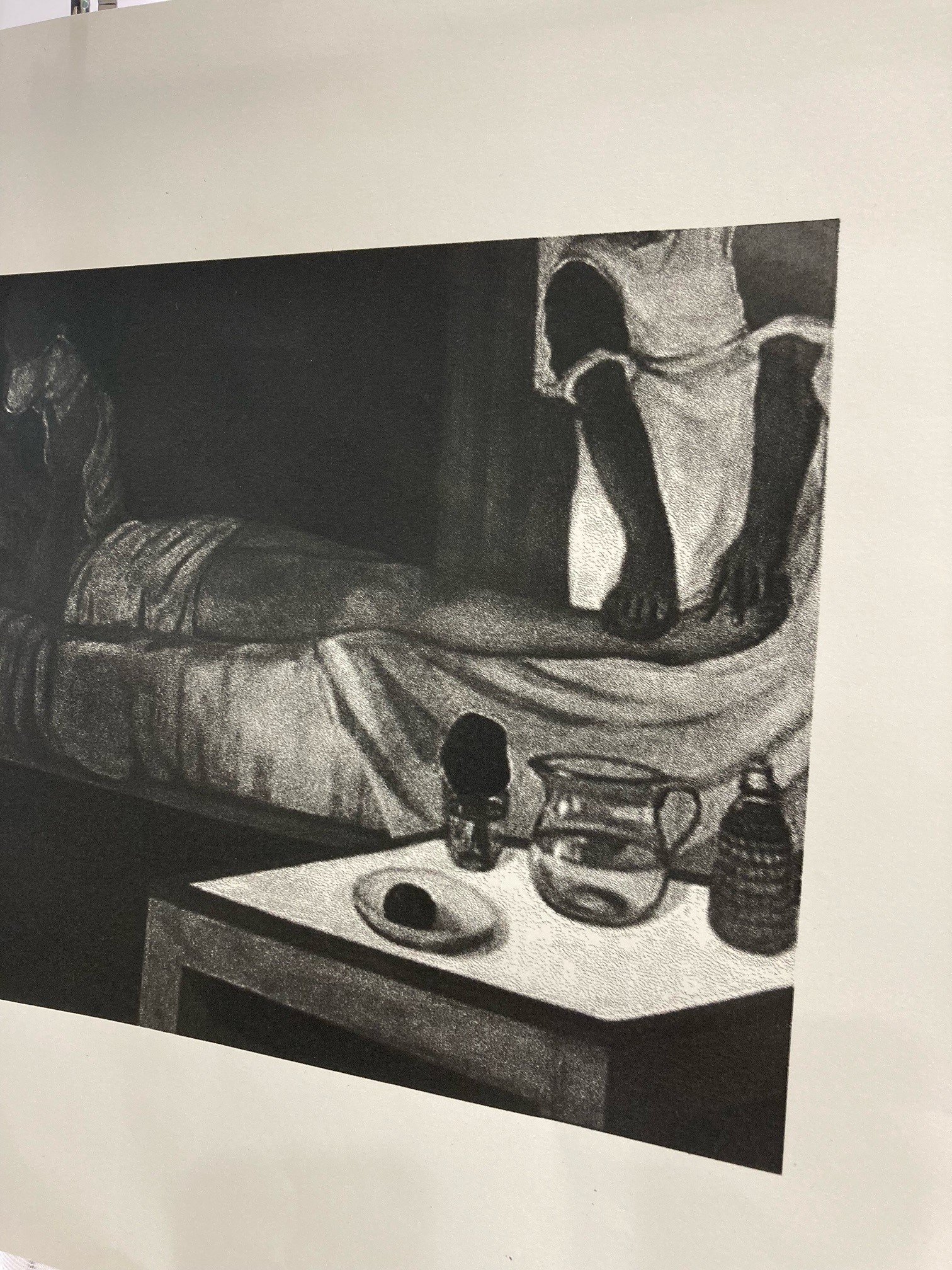

Women at the Lee factory during their sit in.

DENIM – STRIKES, SCOTLAND & STUDIOS

In a post-industrial UK, factory owners looked to downsize and make further cuts to raise more profit around the world through fast fashion and cheap labour, with fewer restrictions or protections for staff, and countries started to compete for this business offering grants and incentives.

The 240 staff at US owned denim factory Lee Jeans in Greenock near Glasgow experienced a shock with news of closure and relocation to Northern Ireland in 1981. The mostly female and young workforce immediately refused to leave, with two of them escaping through a skylight on the first night to fetch 240 fish suppers for everyone on shift. That was the last time they were unprepared, and the sit in became famous and lasted seven months, leading to a management buy-out solution, saving the jobs of the 140 workers still ‘sitting’ inside the Factory. Sadly, this only stalled the subsequent closure which finally came in 1983.

Dave Sherry

A union representative of the time for these women, spoke to us, and said:

‘Our soundtrack was Punk, and Elvis Costello, and for me I remember the band Madness. It was anarchy and drama everywhere, strikes in every major factory or place, and Unions and staff were up in arms trying to prevent closures and job losses.’

In 2002, Levi Jeans in Dundee, who had set up in1972, told the 462 strong workforce of women to go home at lunchtime and stay away until further notice over Christmas. In the 1990’s the site at Broomhill Road employed over 600 locals, mostly women, sending out over a million pairs of jeans per week. It had been part of the new post-war ‘she-town’. The company’s Bellshill premises was also under threat, bringing the total loss of jobs, mostly women’s, to 647 at the time of closure, with the company citing the cost of production –namely wages –when they could source cheaper production and lower wages abroad to make more profit. Dundee –our home city, which had held on to manufacturing in some ways for far longer than many other Scottish cities, and still hosts many major factories such as Halley Stevensons, saw a union brokered deal earning staff redundancy packages still described as some of the best on record. The average worker had been twelve years in Levi’s Dundee, and was offered a year’s salary, or two years’ salary for people with over 30 years’ service, plus additional pay for those helping to wind down the factory. The Unions helped ensure all the women and staff received money, or jobs, help and support. Today, there is a fast-growing market in craft or renewing denim, which has also been exposed as a major user of fresh water – there are no new denim factories, HUIT Denim is in Wales, but we have women-owned and managed social enterprises and brands employing smaller groups of other women and workers in studios from diverse background, such as ReJean Denim –who recycle, reuse, and repair to create new fashion garments which sell out.

A. & J Macnab Ltd, tweed mill on the Tyne, Haddington.

Stephan Brentzler

‘An old friend of mine, he was a Jewish man who came across from Vienna in the Kindertransport during the war.

He was 12 years old when he arrived and was adopted by a family in Portobello, Edinburgh. They treated him like one of their own, and he had a good upbringing.

He later moved to Haddington, which is where I met him. He worked in the tweed mill here for many years before retiring. There used to be so many mills in town, but we only have one flour mill now.’

A woman at work at meadow mill, which is the home of Dundee’s wasps studios.

Dreamland

During the research for this exhibition so many threads linking generations emerged within our contemporary community. One of Dundee’s designers we spoke to, Ruby Coyne, who runs Dreamland Clothing, shared her Nan’s story with us.

Margaret Coyne

Worked at Coldrum Works and Hillbank Mill in the 1950’s. It was all women working on the mill ‘flett’, or the flat –the floor to us, but all of the management were men. Margaret kindly shared some memories with us:

‘The atmosphere was great, just lots of busy women, working away. No music playing - over 500 looms operating. We actually used sign language! This meant I wasn’t a big music lover –preferred the silence after the noise of the looms knocking for 9 hours.

I adored it, I was happy in the company but liked getting on with my own job. In my own wee world. All I can say is –when it was good it was good, but when it was bad it was really difficult to muster through it. It could also be very dangerous. There was no health and safety back then. It was a good life, but a hard life.’

Ruby COyne

This is in synergy and direct contrast to Ruby’s contemporary studio, which is more in line with pre-industrial practices of small groups making music and clothing all day, and is situated on one of the mills her Nan used to work in. Dreamland Clothing has two different lines, one designed and made by her team of Dundee women, inspired by the bold prints of the 80’s. And another line of hand selected and upcycled vintage pieces. She told us about the soundtrack of a day in the studio:

‘We listen to a lot of instrumental music. A lot of Pixar and Disney instrumental - it helps us get lost in our work. And a lot of 80s synth - as this resonates with the task in hand.’

Ruby’s assistant in their Dundee studio.

EXHIBITION VISITOR FROM COVENTRY

“Nylon first arrived in a big way to the UK from America to make parachutes in the war. My father was put to work in the factory in Coventry for DuPont, he was on fire duty the night the Cathedral was bombed.”

“Terrible how many Singers were thrown away, if everyone still had them and knew how to use them the world could be very different. They’re so valuable.”

VISITOR FROM DUNDEE

“My Gran, my Dad, my brother, both my Auntie’s - they all worked at Cox’s Jute Mill at Camperdown where the Home Bargains shopping centre is now, up Lochee. The McManus has photos up the stairs, glad to see them in here.”

Cox’s outlasted closures affecting other Mills until eventually winding down during the Thatcher government’s deindustrialisation policy in 1981, losing its final 340 jobs. Polypropylene and other oil-based products replaced a lot of Jute’s original use for rope or carpet backs among other things. Combined with cheap labour overseas, this saw the final collapse of an industry which at one point had expanded the city during industrialisation to the point where it employed 40,000 families just in Dundee - aka ‘Juteopolis’.

Dundee’s current central population is 148,750, as a city serving a local wider region of 490,000 people, and it has still a variety of chandler, waxed cotton, rope and sail businesses and organisations which serve the population, the creatives, and export goods and services, including VESKE bags, Kerrie Aldo, Montrose Rope & Sail Company, and Halley Stevensons.